On Monday, February 15th and Tuesday, February 16th I delivered presentations to two separate APUSH classes on my independent inquiry. Mr. Welckle was gracious enough to allow me to speak for the first 15-20 minutes of the class, even given the extremely tight AP scheduling such a course demands. As my audience was primarily juniors, I wanted to direct my presentation to inspire other students to engage in their own independent inquiry about whatever they are passionate about. I touched on the content I had been researching the past semester but then delved further into the opportunity ASIJ offers for independent learning, the privileges and pitfalls of that endeavor, and concluded with the fundamental importance of learning history. My slide presentation can be viewed through Google Drive.

Concluding My Inquiry

Now that the first semester is over, it’s time to wrap up my inquiry. I’ll return to the primary questions I laid out at the beginning of the semester to recap the knowledge I’ve gained. Then, I’ll reflect on the holistic inquiry experience and the historian skills I’m developing.

My exploratory question for the Gilded Age was: How does the Gilded Age reveal compelling themes in American culture and how are these trends still applicable today? I spent a significant amount of time examining a “cultural clash” in the Gilded Age between labor and capital, wherein both sides attempted to define American idealism. I concluded that the industrial forces of capital were ultimately successful, and related this historical evidence to modern wealth inequality and the idea of a second Gilded Age in the modern era. In particular, wealth inequality has been a critical focus in this inquiry; I connected wealth inequality to political science research and political theory.

I restructured my inquiry mid-semester to focus on the Great Depression, but was inspired to research immigration during the Gilded Age by the current Syrian refugee crisis, allowing me to make another modern link. I looked at urbanization during the Gilded Age in key American cities and further studied political economy, a new concept for me. Finally, I researched Cobdenism in Britain and America and used my knowledge of economics to better understand the impact of free trade ideology on American isolationism and global responsibility. The overall themes I identified in the Gilded Age and connected to modern society, then, are, among other subtleties: American idealism, wealth inequality, political theory, urbanization, immigration, free trade ideology and isolationism.

My exploratory question for the Great Depression was: How did the Great Depression alter American economic and political ideals, and to what extent are those ideals still relevant in modern America? I began by connecting my idea of American global responsibility to the 1920s and 30s financial system and its ensuing meltdown. I later followed this up with a second post exploring the theme. I then discussed one of the critical functions of the New Deal, which was a changing perspective on the role of government in the economy; I connected this significant historical trend to modern opinion on government intervention. I also examined social security, which originated during the Great Depression as a long-term economic sustainability program. I contacted historian Eric Rauchway to discuss the enduring legacy of Herbert Hoover in the Depression and did a two-part series on the topic (here and here).

From there, I researched FDR quite heavily, analyzing his policies regarding big banks and the general progression of the New Deal during the 1930s. After examining many economic and political ideas, I delved into the rural perspective of the Great Depression through farming lifestyles. Afterwards I deviated slightly from my actual inquiry, writing about World War II spending and the significance of Eisenhower’s farewell warning to contemporary society. I returned to explore the environmental perspective of FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC); in modern connections, my work culminated with a final critique of the New Deal, the importance of a thriving American political left, and the lessons Obama learned (or didn’t learn) from his democratic predecessor in FDR. The overall themes I identified in the Great Depression and connected to modern society, then, are, among other subtleties: American global responsibility, government’s role in the economy, big banks versus rural lifestyles, the New Deal’s effectiveness, the CCC and the environment, and military spending in the 1940s.

In exploring the Gilded Age and the Great Depression at a more intensive and nuanced level than I had done previously, I was definitely able to approach the historical content in those time periods with a critical and analytical eye. While researching I actively applied my argumentative skills to dissect the perspectives of other historians and compare them to one another; then, I could articulate their positions and my resulting ideas about the topics. For example, my idea of “American global responsibility” arose from other historians’ writing on isolationism and protectionism in American political and economic history. I significantly deepened my understanding of American history and society through my modern connections, allowing me to become a better historian. I did have trouble developing my “personal learning network” although I did meet and converse with Mr. Thornton; I also did not engage much with primary sources, choosing instead to delve into secondary sources by other historians. So, those are areas I can look to improve in as I continue seeking excellence in this field of study.

I would definitely recommend other students to create their own independent inquiry about a topic they’re passionate about or interested in exploring beyond the classroom; the opportunity to construct one’s own learning for personal and intellectual enrichment is immensely rewarding. I will likely add a post about my final presentation sometime during January or February.

Meeting with Alumnus, Michael Thornton

One of the primary goals of an ASIJ Independent Inquiry is to develop a “personal learning network.” This network serves to complement the research and independent learning by providing the student with connections to others in their specific field. As my field is history, I had a difficult time developing a network beyond campus. I reached out to several authors and historians, including those who had written some of my texts, but only received one reply from Mr. Eric Rauchway of UC Riverside, with whom I discussed President Herbert and President Roosevelt during their respective stages of the Great Depression. I contacted ASIJ’s Communications Department, which I have collaborated with in ASIJ TV and AP Research work, to help me find others to communicate with. Mr. Michael Thornton, an ASIJ alumnus, was kind enough to respond.

Mr. Thornton graduated from ASIJ in 2005 and attended Yale University as an undergraduate, majoring in history. He is currently completing his history dissertation in Meiji Japan at Harvard University. At Yale, his senior thesis examined Muslim presence in 1900s Japan. However, he spends much of his time now in Japan doing research, locating sources that he would otherwise not find. The Communications Department put us in touch with one another, and we met for an informal conversation in downtown Tokyo in mid-December. Although Mr. Thornton does not specialize in the American historical fields I am looking at in this inquiry he was highly interested in my work, as Independent Inquiry did not exist at ASIJ when he was a high school student. He took a similar interest in my AP Research investigations into Asian American political participation at ASIJ, as the Capstone Program is essentially mirroring much of the research work he has already completed as an undergraduate. We discussed in-depth ideas such as: a second Gilded Age caused by the Information Age, Thomas Piketty’s book Capital in the 21st Century, which is now on my reading list, and the broader intellectual history of the American Dream.

Afterwards, I asked Mr. Thornton several questions about his own experience studying history at institutions of higher learning. Because I am quite certain I want to pursue a history major, I was particularly intrigued by the opportunity to hear what that process was like for a student currently pursuing the highest level of scholarship in historical fields. Mr. Thornton focused specifically on the difference between high school history and collegiate history. While high school history can often be very factual or superficial, he had found that learning history was much more intellectual or quantitative at Yale or Harvard, depending on which track one decided to go down. In his case, he had pursued an intellectual approach, studying ideas and concepts throughout time, rather than a quantitative approach, which might involve more economic or political science investigation. In addition, collegiate history, Mr. Thornton said, involves a much higher degree of research and writing; most of his undergraduate classes involved locating primary and secondary sources and using them to articulate arguments, or building arguments on the work of other historians. This historiographical practice is really intriguing for me, and makes me even more excited to begin pursuing history in college!

Did Obama Learn From the New Deal?

2009 and 1933 have striking similarities in America. Both dates bore witness to major economic crises and an ensuing recession. Also, both dates saw a unfavorable president exit the Oval Office, replaced by a charismatic newcomer who promised to bring about change: FDR in the Great Depression, and Barack Obama in 2009. Due to the similarities between both historical periods, scholarship has examined the links between them. In an article from The Journal of Historical Association, Tony Badger argues that Obama did not learn some of the fundamental lessons the New Deal presents for modern America in times of economic uncertainty. This is partly the fault of the Obama administration, and can partly be attributed to historical trends.

The Obama Administration has not been able to unite both parties under its agenda to any degree compared to FDR’s presidency. In 1933, the Great Depression immediately affected both parties’ constituents. Much of the industrial labor force was unemployed, while farmers and homeowners lost property and credit at an unimaginable rate. Without a system of national welfare, the resources available to charity efforts and local governments (as advocated by 1920s Republicans) were simply incapable of stopping the bleeding. This sense of desperation was critical in galvanizing politicians of all spheres to support FDR in his efforts to bring the country out of the Depression with his New Deal policies. But that feeling was not present in the same magnitude during the 2008 crisis. The Obama Administration did not, to some extent, apply enough pressure on Congress holistically to rally behind stimuli packages for the economy. As such, it could be argued that the Obama Administration’s inability to overcome enduring political polarization in the United States has directly contributed to the lessened resolution of the 2008 crisis.

There is, however, another reason the Obama Administration’s response to the 2008 crisis fell short of ultimate expectations, and it lies in historical trends beginning from the Great Depression. FDR’s response to the economic crisis of the 1930s fundamentally altered Americans’ perception of government intervention: in essence, the government became responsible, to a greater extent than ever before, for the well-being of the economy. In the early 1960s, a significantly high percent of Americans had faith in the government’s ability to do so. One can see why they held this faith: their government had, in recent years, brought the nation out of the Great Depression, won World War II, and established itself as a supreme power in the world. But that faith was shattered in coming years, largely due to the Vietnam War and presidential controversies, such as the Watergate scandal during the Nixon Administration. While Roosevelt was fortunate enough in timing to transform America’s perception of government, Obama has brought about such a cultural shift during his presidency. In fact, public trust in the efficiency of government is, in America’s eye, at an all-time low.

Cobdenism: A Free Trade Ideology in the Gilded Age

While reading an article from the Diplomatic History journal written by historian Marc-William Palen, I came across a term I had not seen before: Cobdenism. Apparently, Cobdenism originates from the ideologies of a British individual named Richard Cobden, who advocated free markets and free trade worldwide. The overarching belief of Cobdenism holds that international free trade will ultimately lead to global interconnectedness and world peace. Although I am unsure why this term is not used commonly anymore, I believe it bears many similarities to Adam Smith’s theory of capitalism. Adam Smith’s capitalistic ideals arose out of a backlash against mercantilism and other such economic systems he deemed misguided; he instead stressed that minimal government involvement in a laissez-faire (let it be) economy, dictated by an invisible hand controlling the market, was optimal for societies. Because Cobdenism originated in the late 1800s of the Gilded Age (much later than Adam Smith’s ideas) I believe this term applies to the free market ideology that complemented Britain’s imperial dominance at the time.

While Cobdenism grew heavily popular in Britain during the late 1800s – there was even a Cobden Club in London, with sects existing abroad too – such an ideology of international economic openness was heavily opposed in America. After the Civil War, America still retained aspects of its previous international identity from the Monroe Doctrine, which instigated longstanding policies of isolationism for the nation. There was thus strong opposition to the ideals of Cobdenism from American protectionists. In economics, protectionism is essentially the opposite of Cobdenism: it stresses a restraint of trade between nations through means such as tariffs, quotas, and other government regulations. American protectionism in political spheres during the Gilded Age was thus a lasting continuation of American isolationist tendencies, which existed beforehand since the Monroe Doctrine and afterwards too. In fact, I would argue that American isolationism only truly ended with the advent of World War II, which thrust America into international power (along with the USSR) and outlined the nation’s global responsibility.

American protectionism, I believe, goes hand in hand with anti-immigrant sentiments. In a previous post, I discussed the importance of immigration during the Gilded Age and, truly, throughout American history. But American protectionism also developed an association with Anglophobia itself, or the fear of British influence in the United States, a national feeling that carried over from the nation’s origins, namely the American Revolution. As such, cultural, political, and economic tendencies in America’s Gilded Age intersect. America’s cultural antagonism to immigration coincided with political opposition to foreign economic ideals. Interestingly, though, one of the key features of American history is that of accepting the unacceptable: for example, while some politicians may argue against certain aspects of immigration, America has been built by immigrants since its founding. Similarly, the United States was heavily isolationist and opposed to international involvement for much of its history; now, though, the United States is the most pivotal international player, having succumbed to global responsibility. I think this analysis of Cobdenism effectively ties together different themes in American history, particularly during the Gilded Age, and hints at a broader historical idea of what it means to transform as a nation over time.

Wealth Inequality, Political Science, and Locke’s Theory

Wealth inequality has been one of the primary topics of investigation during this inquiry. In an article from the Social Science Quarterly, Thomas J. Hayes examines the link between public policy preferences and a societal understanding of wealth inequality. The gap between the rich and poor has steadily increased since World War II and represents one of the greatest current threats to American democracy, which has led researchers to examine the American public’s perception of the issue and its relation to contemporary politics. Indeed, many consider modern America to be experiencing a second Gilded Age, corrupted by oligarchic tendencies. Hayes’ research examines the public’s ability to relate wealth inequality to the political platform, and the resulting effectiveness of that link in changing policy. I personally find this scholarship intriguing, although it is not entirely related to history. I am strongly considering pursuing a degree in political science (in addition to history) and my AP Research work is in the political science field.

Hayes notes the impending importance of the public in combatting wealth inequality. If American citizens are unable to link rising wealth inequality to the political scene through issues such as taxation or redistributive programs, Hayes argues, alleviating longterm inequalities will continue to be a critical problem for the nation. This perception is understandable: if the common people cannot (or simply do not) convey their preferences on issues of equality or any other focus to elected officials, the core tenets of democracy will stagnate. This is in keeping with even the most basic of political theories, such as John Locke’s philosophy articulated in his Two Treaties of Government. In Locke’s view of human nature and political well-being, the people must exist as the ultimate power in a free and equal society; government, he believed, must answer to the people. However, this sort of political system will not operate to its full potential (if at all) if the people are not capable of, holistically, accepting responsibility for society itself. It was this weakness in Locke’s political theory that led other theorists, such as Thomas Hobbes, to argue that humans were essentially evil and incapable of governing by the will of the masses.

This approach to understanding the modern issue of wealth inequality connected the issue to my studies in AP European History regarding major political theories and ideas, an interdisciplinary connection that I find fascinating. Hayes employs advanced political science techniques in his collection of data, which I won’t elaborate on too much here (although I hope I can reach that level someday) but his conclusion is both positive and negative. While Americans tend to draw connections between wealth inequality and spending preferences by both the federal government and local political actors, the public is, by and large, unable to bring about meaningful political change as a result of that understanding. This essentially means that, when considering wealth inequality, the common people are not fully fulfilling Locke’s vision for society. While I think it is unlikely that this divide will lead to a disintegration of political or socioeconomic order in America, it’s definitely an issue worth advocating in order to improve overall quality of life. After all, only an extreme minority of Americans actually benefit from wealth inequality.

Approaching the Semester’s End

As the first semester of senior year draws to a close, I need to bring my inquiry together and develop answers to the driving questions I formulated regarding the Great Depression and, to a lesser extent, the Gilded Age (note I decided to refocus my inquiry on the Great Depression earlier, as articulated in this post). My requests to have final presentations given to both an APUSH class and a teacher/interested student audience have been granted, and those will occur during the onset of the second semester. Winter break presents the optimal opportunity to conclude the content-driven aspects of my inquiry and engage in thorough reflection and presentation-planning. So, I am going to finish my research and writing towards the end of December and finalize my ending presentations thereafter. I think I will include information about my reflections on this blog, as those will inform my presentations too.

Urbanization During the Gilded Age and Political Economy

The Gilded Age allowed for rapid urbanization of American cities through wealth concentration and developing industrial technology. In an article from the journal Planning Perspectives, urban historian Domenic Vitellio examines the history of urban planning in the Gilded Age as it relates to centralization of power and authority: essentially, how urbanization grew increasingly central to American life during a time of immense socioeconomic change. I personally find this lens to be very intriguing because I have never before considered viewing history through an architectural or urban perspective. In Philadelphia especially, newcomers such as Peter A.B. Widener were able to usurp political power in the late 1800s and early 1900s, allowing elite groups to remake the socioeconomic structure of city life. Such individuals, among them also Charles Yerkes in Chicago and William Whitney in New York, exercised enormous power over American city developments during the Gilded Age.

In previous posts, I established that the idea of monopolies was central to Gilded Age life. In a sense, urban planning was dominated by a monopoly of its own sort, spreading to multiple cities across the nation and spurred onwards by growing wealth concentration (which, generally, was also accompanied by rising inequality). Much historical scholarship focuses on the portraits of singular individuals such as Widener who wielded great power in urban development through corporate or social means. But even so, different cities underwent widespread patterns of urbanization, a phenomenon that can be attributed to the variety of factors beyond the control of even monopolists. Such factors can include: minute discrepancies in local politics, competing technological developments, ideological impasses, and so on. While it is true that certain individuals carried a great degree of influence over urban development during the Gilded Age, to say that the patterns of growth experienced in cities from New York to Chicago were identical would be historically inaccurate and insufficient.

The article goes on to discuss urban developments in American cities in a great deal of depth; however, the introductory stages delve into the idea of “political economy” which is a phrase I have read and heard about before but only ever superficially considered. According to Investopedia, political economy is “the study and use of how economic theory and methods influences political ideology.” This strikes me as very interesting, but also quite complex, as it would require a perceptive understanding of both economic theories and political ideologies. Game theory is also a significant part of the political economic field, as it allows groups and individuals competing for finite resources to devise the best potential outcomes for profit, or any other goal in mind. This reminds me of the definition of economics itself that I learned last year: “the study of allocating scarce resources to satisfy human wants.” I am wondering now how a historian might connect urban planning to political economic theory. In any case, this exploration has reinvigorated my excitement to get back into economics with AP Microeconomics in the second semester!

How the American Left Conceived Structural Reform During the Great Depression

In his essay “The Past, Present, and Future of the American Left,” author Eli Zaretsky rebuts the claim that America does not need a political left. This claim is based on the idea that America is, by its nature, liberal, and thus does not require a strong political left on an everyday basis. Zaretsky aims to explain why liberalism is needed in America, using historical analysis to justify his points. He likens American history to a suspension bridge held up by three long-term thematic crises: slavery, industry, and finance. Personally, keeping with this inquiry’s guidelines that I established, I’m particularly interested in how Zaretsky justifies a modern American left through the Great Depression, a period of near socialism in American governmental policies.

The Great Depression ultimately resulted in structural reform of American government by creating the notion of a welfare state: essentially, a government that would actively involve itself in economic affairs for the intentional benefit of citizens. Zaretksy points to a long term history of recessions and economic panics in America dating back to the Civil War that had become systemic in nature. These reoccurring crises could only be corrected through a structural transformation of American life, a transformation initiated by the onset of the Great Depression, certainly the worst economic crisis in American history.

Zaretsky articulates his belief that a modern and influential nation-state could still have been created without a socialistic perspective on American government which originated during the Great Depression in FDR’s administration. This socialist ideology, however, did infuse the New Deal with a need for egalitarianism and socioeconomic equality between Americans. Just as the abolition of slavery perpetrated the ideal of racial equality among Americans, the New Deal and Great Depression brought awareness to a need for socioeconomic fairness of opportunity in America. But at the same time, neither historical process has culminated in success: many intellectuals, such as Columbian professor Eric Foner, one of my favorite authors, argues that Reconstruction’s unfinished legacy has directly impacted American race relations today. I think the same can be said about the Great Depression and modern American inequality, which I explored in a previous post.

Although I personally am not entirely convinced by Zaretsky’s assertion that socialism was not necessary for creating new perspectives on government intervention, I do think the argument he makes in regard to the American left is significant. The social and cultural revolution launched by the New Deal and its relation to government intervention definitely gave rise to a prominent American left that has remained in American political life ever since. Because such issues like wealth inequality and racial tension remain, America cannot be considered liberal by nature anymore (though that was perhaps true hundreds of years ago); An American left is needed to continue advocating the ideals America has always attributed its existence to.

Critiquing the Effectiveness of the New Deal

In his article “New Deal Denialism” Eric Rauchway notes that rightists and leftists harbor conflicting viewpoints on the Great Depression: rightists argue that the New Deal was a jumble of ineffective socialist policies, while leftists retain that the New Deal did bring some degree of reform for Americans. But Rauchway argues that evidence from the time period does not directly support either contention, and thus in order to learn from the history of the Great Depression, the actual effectiveness of the FDR’s policies must be more closely examined. He relates this to modern attitudes about the 2008 Recession and possible a new era of depression, which I found to be a significant modern interpretation of New Deal history.

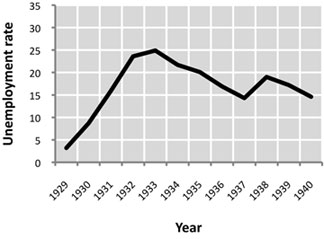

Firstly, Rauchway analyzes fluctuations in American GDP during the Great Depression. While the New Deal did not fully end the Great Depression without the aid of World War II, America’s GDP was steadily increasing throughout the 1930s, a sign that the country was very much on the road to recovery. Economic growth during New Deal years averaged to being between 8 and 10 percent; such numbers ought to be considered spectacular, given the state of the American economy in a severe recession.

Rauchway argues that New Deal policies did not fully pull America out of the recession during the 1930s due to the immense and unprecedented magnitude of the Great Depression, the likes of which had never before been seen. It is therefore possible that FDR’s New Deal policies did not allow for optimal recovery, although recovery did occur. An examination of the New Deal must therefore consider how Roosevelt could have adopted better policy, not whether he adopted any good policy at all.

In the 1930s, methods for measuring unemployment were much different from modern constructs. As such, using unemployment rates to analyze the New Deal is often a retrospective and deductive task, though not any less worthwhile. Although much data suggests steady improvement of unemployment levels during the New Deal, there is an inherent need, Rauchway argues, for artificial federal employment (such as through the CCC or other organizations) be separated from legitimate economic employment, such as private or farming activities. Even so, the unemployment situation appears much more favorable under FDR than under Hoover during the Depression’s early onset.

As unemployment is critical to determining GDP, to argue that the New Deal did not aid in American economic recovery would require making assumptions based on data generally agreed upon to be false, something that many conservative commentators had done after 2008 to protest imitations of FDR’s policies. I personally found this information very interesting because it ties largely into some of the economic ideas I’ve learned as well as historical processes, developments and interpretations.

Roosevelt’s policies during the Great Depression were certainly not perfect; many scholars agree that the onset of World War II saved his presidential legacy by turning the page on the Depression. His policies ought to have done more for minority groups and lower class citizens, as articulated in a previous post, and did not contribute to recovery as significantly as they perhaps should. However, it must be acknowledged that FDR’s administration, although demonized as being socialist at times, did take measures to lift America out of the Great Depression. Any analysis of the New Deal must take this into account when interpreting “what if” scenarios and articulating how the New Deal could have been better implemented to achieve its goal of American recovery and prosperity.